By Caitlin Hollander

Last November, I participated in a cemetery indexing project in one of the sections of Mt. Zion Cemetery in Queens, New York that had become overgrown and neglected when the burial society that owned it had gone defunct. There, a grave caught my eye- while the motif of a young tree cut off before its prime is a common one in Jewish cemeteries, symbolizing a young life that had ended too soon, this particular grave was one of the most beautiful, intricate examples I had ever seen. Only a few graves in this massive cemetery- totaling over 210,000 burials- were in the same unusual style. But this grave, of a young man named Solomon Schreiber, captured me. And so I decided to research who this boy was and what caused him to meet such an untimely end- and who the family was that memorialized him in such a poignant way.

The grave of Solomon Schreiber at Mt. Zion Cemetery in Queens. Photo by the author.

All I had to go on was his name, age, date of death, and his father’s name from the Hebrew on the grave: Aron. At first, I couldn’t find any death record for him, nor any census. But then I widened my parameters, and sure enough, I found a misindexed 1900 census record. And there he was.

Solomon Schreiber. Born in New York, only a year old. The youngest of the seven living children (there had been eleven total as of this census) of Aron Schreiber and his wife Kate. Aron was a butcher and Kate, a housewife. His older siblings- Ida, Annie, and David, all born in Austria, and then Jacob, Harry, and Louis, born in New York. Another Jewish immigrant family living on the Lower East Side. The family seemed fairly well off; of the children, only Annie, age 18, worked. So, I followed the trail forward to see what had happened to this boy with the beautiful grave.

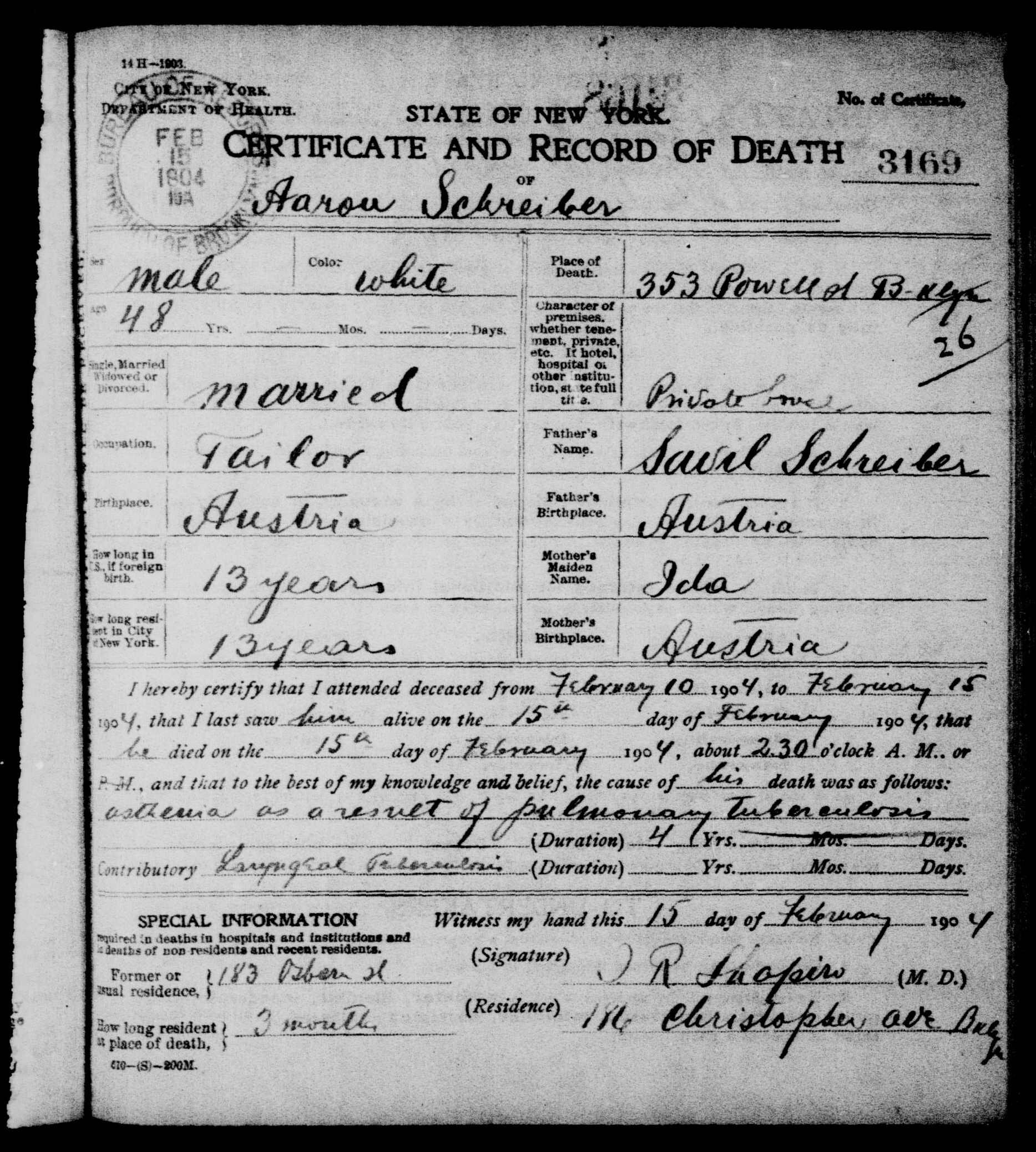

Here was the first tragedy- by the 1905 New York State census, the family dynamic had changed quite a bit. The household consisted of Kate, and her children David, Jacob, Harry, Louis, Solomon, and another daughter, Fannie. Kate is listed as a widow. And while in 1900, the only child working was over 18, in 1905, not only 18-year-old David but also 15-year-old Jacob are working- a sign of the family’s changing fortunes. A quick search provided the reason- 48-year-old Aron’s death after a four year fight against tuberculosis. Solomon would have been not yet six when he lost his father.

The 1910 census is much the same, except for a tragic note beside Kate’s name. This is the last census in which women were asked the delicate questions of “how many children have you given birth to?” and “how many are now living?” (something that would be unthinkable for the census to ask today). Kate’s answer to the former is fourteen, and the latter is eight, meaning that she had lost two children since 1900 in addition to having her youngest daughter. Jacob, Louis, Harry, Solomon, and Fannie are all at home. Louis, at 14 years old, is no longer in school but working as an office boy. His two older brothers are also working; only Solomon and Fannie are in school.

So then the question: how did this young man die?

I finally found a death certificate for one Samuel Schreiber, dated for the same date on the grave, a naval enlistee who died in the naval hospital in Great Lakes, Illinois- the location of the navy’s only boot camp. His body was shipped back to New York. No parents were given on the death certificate. And yet, I was sure that this was Solomon. So I pulled the WWI Naval Casualties record. Even though he did not die at war, or even graduate boot camp, he would be there. This gave me a next of kin: a John Schreiber in Freehold, New Jersey. Looking at Solomon’s siblings, Jacob was the most likely candidate to anglicize to John, and I had the name of his wife. And sure enough, on the 1920 census, he is living in Freehold. Over the years, he alternates between Jacob, John, and Jack. But this was a solid confirmation that Samuel Schreiber and Solomon Schreiber were one and the same.

As is all too common in genealogy, the answer to that question only gave rise to more questions. Why did Solomon join the naval reserves in Philadelphia? Why was his next of kin his brother, and not his mother? Had he run away to join the navy? Sadly, these are the type of questions that cannot be answered, and while I can speculate, we will never know for certain. If Solomon had run away, with only his brother knowing, did Jacob blame himself for his brother’s death?

This article was originally going to be about symbolism in Jewish graves. I had a collection of graves with the same cut off tree motif, short biographies of each of them. But something about Solomon/Samuel Schreiber kept drawing me back to him.

And then, four months after I first saw his grave, I got COVID-19. I had a bad case and I was sure I was going to die. Far from my family and where I grew up, sick in a pandemic, and absolutely terrified.

And I thought of Solomon.

He, too, was far away from home when he became ill in a pandemic. I survived, he did not. 102 years separated our respective illnesses; he, from the Spanish Flu, me, from COVID-19. And while I can only imagine how he felt in that hospital in Illinois, over 800 miles from home, I think I know a little bit. That fear that you will never see your mother again, never hug your siblings. That every time you close your eyes, you might not wake up. The shivering from fever, the gasping for air. Every hacking cough that feels like your chest is going to crack. And that deep, eternal fear that something terrible is lurking around the corner, and the profound loneliness of going through it all without a familiar face or hand to hold.

I wonder about Kate, and how she handled her youngest son dying so far away from home. One look at this grave tells you how deeply this young man was loved. His family was not wealthy, but his grave is beautiful, designed with care. From the American flag on the upper left to the phrase “my beloved son and our dear brother”, every bit of it is designed with care. For a family that would not have had much money, they scraped it together and ensured that Solomon would have a fitting grave.

Kate would lose another child the following year in the same pandemic – Solomon’s older sister, Ida, a 39-year-old married mother of ten children. Ida’s eleventh and youngest child, a boy named Samuel in English but Solomon in Hebrew for his uncle, had died at only four months old that May. Kate herself would die a decade after her son at 70 years old.

Despite him having many nieces and nephews, and they most likely having innumerable descendants of their own, it seems that Solomon is all but forgotten. The only online trees that have his name in them do not record his death- he simply vanishes. His grave does not have perpetual care, and so, when I returned to Mt. Zion in August after recovering from my own illness, the walk to Solomon’s grave was impassible- unlike my November visit, the snow had not yet cleared the weeds. I was able to walk on the path behind him, though, and leave a stone on his grave.

I do not want to be the only person to remember him, the boy with the beautiful grave, and so I bring his story to you- a story befitting of pandemic times of a young man, the New York-born son of immigrants, who joined the navy and died too young of the Spanish Flu, so far away from home.

May his memory be a blessing.