By Caitlin Hollander

Very rarely is a law enacted in anticipation of a disaster; they are almost always due to a tragedy that has already happened. Exit doors in the US legally must open outwards due to the 1903 Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago, which claimed the lives of over 600 people- in part because they were trapped when the inward-swinging doors could not be opened due to the crush of the panicked crowd.

In 1911, the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors of the Asch Building (now called the Brown Building) near Washington Park in Lower Manhattan were home to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which mass produced the on-trend women’s garment. The shirtwaist, which had risen in popularity in the late 19th century, was the woman’s answer to a man’s dress shirt. Mass producing them meant that this fashion trend was accessible to the lower income New Yorker. And just like much of modern-day mass-produced fashion, the workers involved in the creation of the garments were treated poorly, working long hours for little pay in unsafe working conditions. At the Triangle, the mostly young, female, Jewish and Italian immigrant workers earned between $7 and $12 per 52-hour workweek (or about $165-$318 in today’s money, or about $3.17 to $6.11 an hour). This job was coveted for another reason- fires were common in the garment industry, and the Asch Building had been described as “fireproof” (echoing the tragedy of the “unsinkable” Titanic a year later).

This article was posted at 4:40pm EST, on March 25, 2021; exactly 110 years ago to the minute from the moment that a fire broke out on the 8th story of the Asch Building. This fatal fire, which would take so many lives, would forever change the way that American laborers were treated.

Thirty-nine year old Catherine Maltese (born Caterina Camino) was there at work on March 25, 1911, with her daughters, twenty-year-old Lucia and Rosaria, who at only fourteen years old, was one of the youngest employees of the Triangle. They were living at 35 2nd Avenue in Manhattan with Catherine’s husband and Lucia and Rosaria’s father, Serafino, and Serafino and Catherine’s other two living children, Vito and Paolo. According to the 1910 census (which records Rosaria as Sara and Vito as Tom), Catherine and their children had arrived in America four years prior from Italy. The first tragedy occurred shortly after immigration; Catherine and the couple’s youngest daughter, a girl named Maria, were detained at Ellis Island due to illness. While Catherine survived, four-year-old Maria perished before ever getting past this gateway to America. In total, the couple had lost three children; far from uncommon for the era.

The Maltese family on the 1910 US Census. Image via FamilySearch

According to the fire marshal’s report, the fire likely began in one of the scrap bins under the wooden tables of the factory. These bins held several months' worth of highly flammable scraps of fabric. Beyond the issue of flammable rags, conditions in the Triangle were far from safe. The owners had ordered the doors to one of the two external staircases (despite three being required by law, the city allowed the fire escape to count as a third) locked to prevent employees from stealing. That fire escape was narrow and poorly anchored, and could not bear the weight of too many people- something which would prove fatal.

In addition to the dangerous working conditions, the owners of the factory, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, were notorious for their anti-worker policies. When the garment workers union had ordered a strike in 1909, they paid off the police to arrest the striking workers. Upon the end of the strike, the Triangle refused to sign the union agreement. This would’ve guaranteed increased safety and worker protections. After the fire, the unions would have reason to strike again

At 4:45pm, the first alarm was sounded by a pedestrian passing by the building who noticed the smoke. The building had no fire alarms, and the 9th floor had no telephone; so when a bookkeeper working on the 8th floor saw the fire he was able to call up to the 10th to warn the employees there, but the employees on the 9th floor had no knowledge of the fire until it reached them. The employees there would make up the majority of those killed.

On February 5, 1911, six weeks and six days before the fire, a seventeen year old girl named Sarah Brenman arrived at Ellis Island. She was born in the town of Sharovka, now in Ukraine, and had come to America to live with her older brother, Morris (Moshe), who had come to America seven years earlier in 1904. Three other siblings had already come to America; another brother, Joseph, and two sisters, Rosie (Reizel) and Esther. Twenty-three year old Rosie or twenty-one year old Joseph most likely had gotten the job at the Triangle for their newly-arrived sister, as they were both employees of the Triangle and were both there that day.

The foreman with the key to the locked third staircase fled as soon as the flames began. The flames on the 8th floor made it impossible to descend the unlocked staircase, and so some employees used it to flee to the roof until it became blocked both ways. New York University students from neighboring buildings grabbed ladders and ropes; their efforts saved 50 of the trapped workers.

But now, the only staircase remaining that could be used to get out was the flimsy fire escape. The workers crowded it until it collapsed, sending about 20 people falling nine stories to their deaths.

The collapsed fire escape in a photo taken for the official report on the fire.

The only remaining way to escape was the elevators, operated by some of the factory’s few male employees- Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillaro. Even getting to the elevators was tricky, with the long, narrow corridor becoming easily crowded and the language barriers causing increasing confusion.

Joseph Zito, a twenty-seven year old new father had only been working at the Triangle for about six months. He braved the flames and extreme heat- heat which damaged Gaspar Mortillaro’s elevator so badly that it could no longer make the trip- to go twice to the tenth floor, loading his elevator with as many people as he could. When the fire became too great, he continued to go to the ninth floor, and then eventually just the eighth, each time overloading his elevator. On his last trip, he carried 40 people in an elevator with a capacity of 10. In desperation, people climbed on top of the car. The weight proved too great, and the cables snapped.

There was no way out. 62 people were witnessed jumping or falling to their deaths.

After the smoke cleared, the death toll began to mount. The circumstances of the fire made it hard to identify victims immediately; many were taken to Charities Pier by the East River for identification.

In total, 146 people, ranging in age from fourteen to forty-three were killed in the 18 minutes the fire raged.

The bodies of Lucia and Rosaria Maltese were identified by their father the day after the fire. They had been found at the bottom of an elevator shaft in each others’ arms. But Serafino could not find Catherine, and kept returning again and again searching for her.

Due to the state of Catherine’s body, she was not identified until June of 1911. She had, by then, been buried with the other unidentified victims. The Red Cross gave the family the money to have Catherine’s body moved, and she was buried with Lucia, Rosaria, and little Maria in Calvary Cemetery.

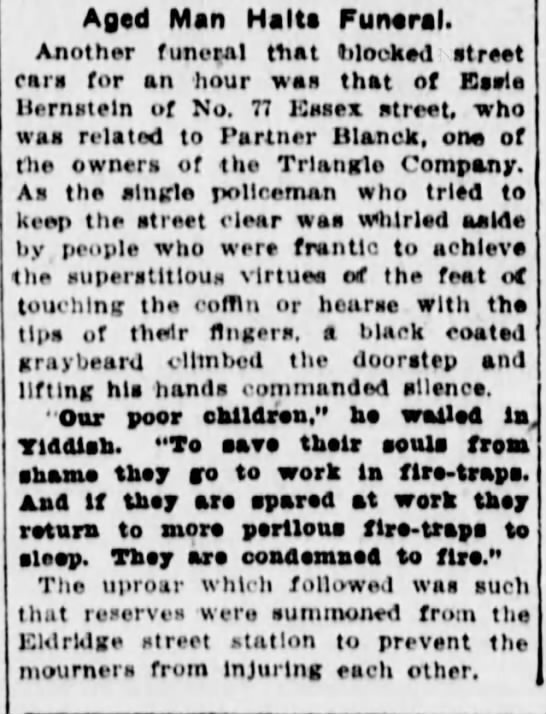

The Evening World, New York, New York, March 27, 1911.

The Star-Gazette, Elmira, New York, March 27, 1911.

Sarah, Rosie, and Joseph Brenman were all employed by the Triangle and were all present on the day of the fire. Only twenty-one year old Joseph escaped. Sarah and Rosie’s bodies were so badly damaged that they both were identified by their teeth; Rosie, by her brother with the assistance of a dentist on March 29, and Sarah, by their sister Esther on April 1.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, March 30 1911. Image via Newspapers.com

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, April 2, 1911. Image via Newspapers.com

Nineteen year old Esther had a nervous breakdown after, according to the Red Cross, who sent money to the family both there as well as to their widowed father, Chiel, and two younger sisters in the Russian Empire. Eventually, the family would be reunited in New York, when Chiel and his youngest daughters arrived in 1922. The girls are buried together at Baron Hirsch Cemetery.

The Triangle Factory Fire and its avoidable death toll elicited outrage, especially from unions, who took to the streets to protest. After the official report was issued, stating that if the doors had been unlocked it was entirely possible that no one would have died, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, both Jewish immigrants themselves, were charged with manslaughter. They were acquitted of criminal charges, but lost a 1913 wrongful death suit and were forced to pay $75 per victim to the families. This may sound just, but they had a $60,000 insurance payout from the fire, so when all was paid they had actually earned approximately $336 per victim.

But Max Blanck’s lack of remorse is clear when, the same year as the wrongful death lawsuit, he was caught once again locking the doors of a factory he owned to keep workers inside. There was a national outcry when he was fined a mere $20 for the crime.

This fire instigated major changes in American workplace safety law. As a result of the fire and the many union protests after, New York founded the Factory Investigating Commission. From 1911–1913, 38 laws for workers’ rights were passed in New York State.

The last survivor of the fire, Rose Freedman (maiden name Rosenfeld) died in 2001 at the age of a hundred and seven. She had been only seventeen at the time of the fire.

Smaller monuments dot the cemeteries where the victims are buried, sponsored by unions and families, but, despite funds being designated for the purpose by the state of New York in 2015, there is still no other memorial to the 146 people who died that day 110 years ago.

May their memories be a blessing and their legacy never forgotten.

Further reading

The elevator operator Joseph Zito, who survived, saved over 100 lives that day. For more information about him, please read this story from WNYC. https://www.wnyc.org/story/119910-family-keeps-memory-triangle-fire-elevator-operator-alive/

Cornell University’s Triangle Factory website is an absolutely invaluable resource for primary and secondary source documentation https://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/index.html

The Red Cross’s full disclosure on the emergency relief after the fire can be found here: https://archive.org/details/emergencyreliefa00charrich/mode/2up?view=theater

OSHA has a page on the fire here, which links to a number of excellent resources: https://www.osha.gov/aboutosha/40-years/trianglefactoryfire

![From the Inquisition of Lisboa processo for Judaizing of Gaspar Fernandes o Gallego. In Portuguese it states “Disse que elle se chama Gaspar Frz gallego, mercador, e que christão novo de idade de sesenta e dois annos…” which means “[the Defendant"] …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d04c37114376000012d52b9/1575405943747-VE2VJG82XNDO3WKTJ134/PT-TT-TSO-IL-28-12135_m0066.jpg)